Open Access

Cognitive Functional Therapy

Research

Below are a collection of research papers about Cognitive Functional Therapy.

Click the down arrow ( ) to access the summary and link to the full open access paper.

Cognitive Functional Therapy: An Integrated Behavioral Approach for the Targeted Management of Disabling Low Back Pain

Peter O'Sullivan, JP Caneiro, Mary O'Keefe, Anne Smith, Wim Dankaerts, Kjartan Fersum, Kieran O'SullivanPhysical Therapy & Rehabilitation Journal, Volume 98, Issue 5, 1 May 2018, Pages 408-423, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzy022

Summary

Section 1 - "Multidimensional Factors Associated with Disabling LBP"

Section 2 - "Cognitive Functional Therapy: Assessment and Treatment"

Section 3 - "Skills Required to Implement CFT"

- Communication skills to sensitively explore how people think and feel about their problem, build strong therapeutic alliance, enhance self-efficacy and promote behaviour change.

- Strong clinical reasoning skills to triage and synthesise multidimensional information.

- Observation skills are required to analyse functional and safety behaviours.

- Hands-on feedback and movement facilitation skills are needed to guide behavioural experiments and teach new behaviours.

- Clinicians need to have confidence to discourage safety behaviours, and to intrinsically recognise that pain is more strongly related to multidimensional factors, rather than damage, that the spine is strong and movement is helpful.

From Fear to Safety: A Roadmap to Recovery From Musculoskeletal Pain

JP Caneiro, Anne Smith, Samantha Bunzli, & Steven J. Linton

Physical Therapy & Rehabilitation Journal, Volume 102, Issue 2, 23 December 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab271

Summary

Fear learning

The common-sense model is a model of fear avoidance and a recovery pathway that has been investigated. Sense-making at the heart of this model goes beyond catastrophising, and includes the 'cognitive representation' of an individual's pain condition informed by memory of their past 'normal' self, pain experiences, treatments, lifestyle and social activities.

- Identity (what is this pain? e.g. structure)

- Cause (what caused this pain? e.g. bending)

- Consequences (what are the consequences of this pain? e.g. disability)

- Timeline (for how long will this pain last?)

- Cure/controllability (can this pain be cured or controlled?)

Safety-learning

- Screen

- Interview

- Examine

- Expose with Control

- Make Sense of Pain

- Integrate into daily life

- Provide an flare-up plan

- Refer if co-care is required

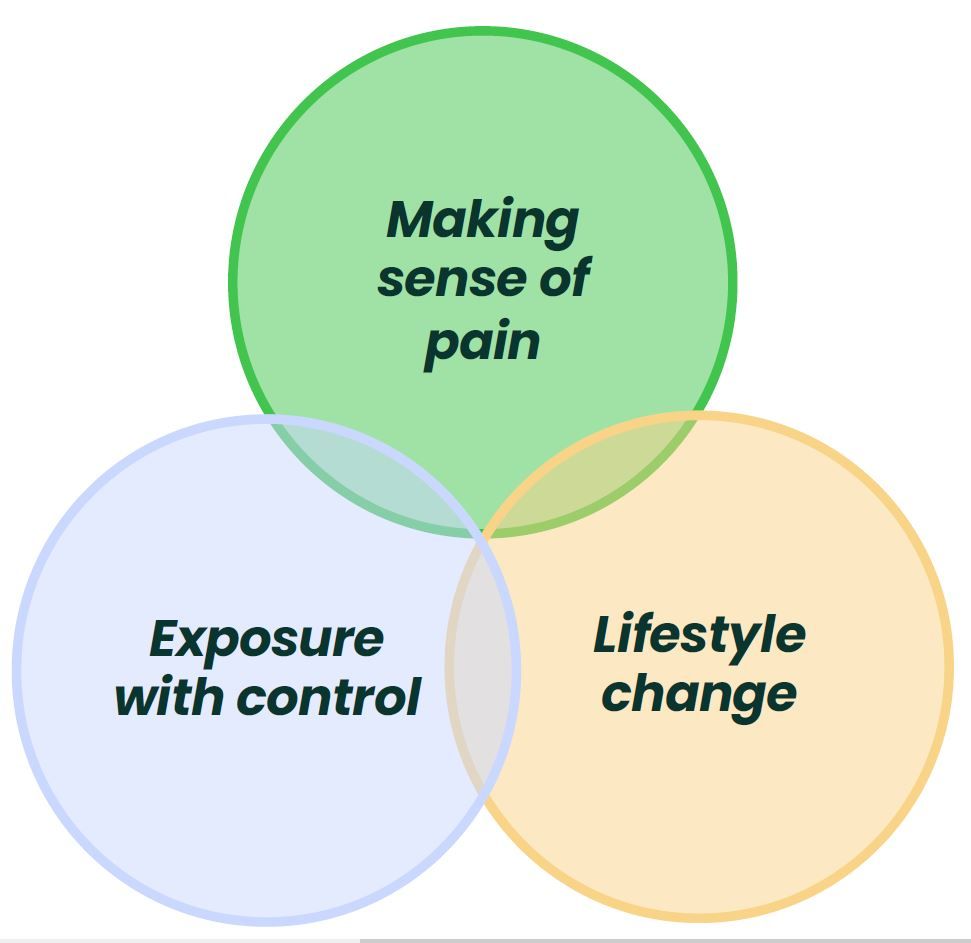

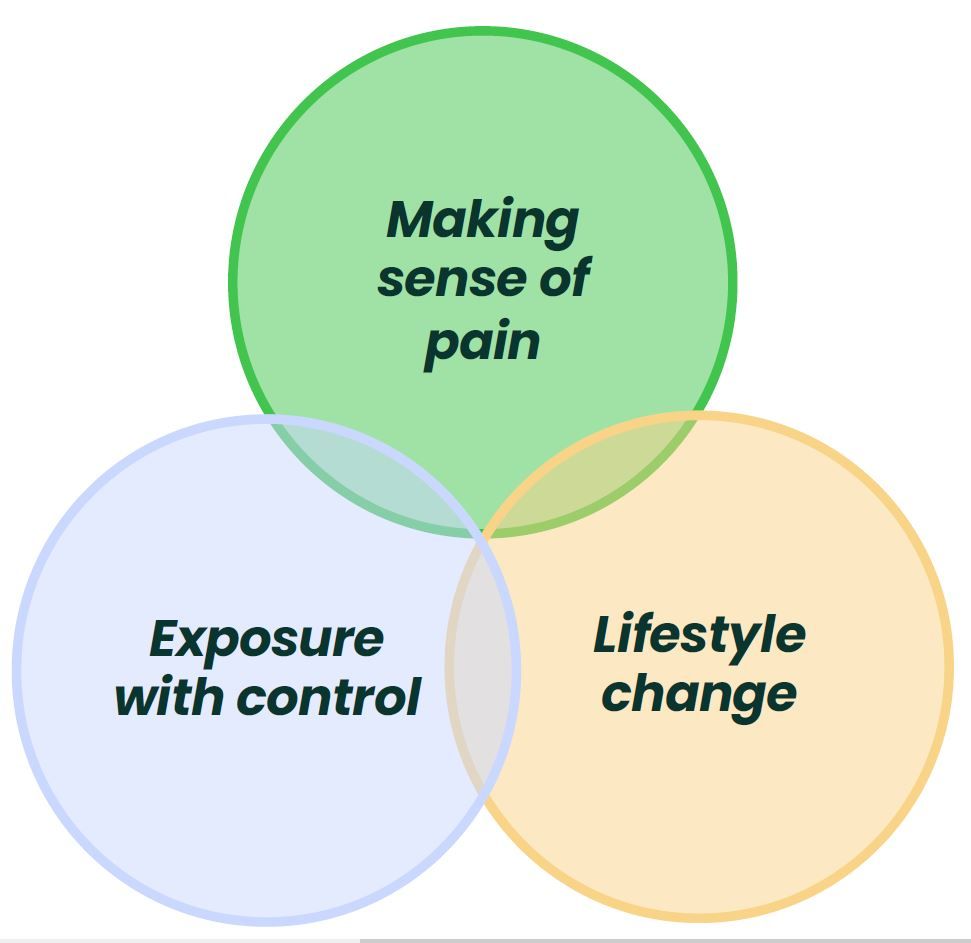

CFT to promote safety-learning

B) Core elements of Cognitive Functional Therapy as a vehicle to promote safety learning. The experience may confirm or violate the original schema. Confirmation of pain as a threatening experience (i.e. learning does not occur) leads to the reinforcement of the person’s fear response. Violation of pain as a threatening experience (i.e. learning of safety occurs) can powerfully disconfirm fear-avoidance beliefs while reinforcing that valued activities can be safely confronted when performed without safety behaviors and reduced pain vigilance. This leads to an update of the person’s response that promotes generalisation of safety.

C) Person’s common-sense response to an experience interpreted as safe (Safety schema).

D) Response to a pain flare, which may reinforce fear or safety learning. This is a crucial learning opportunity that influences a person’s process to recovery.

Patient-centered consultations for persons with musculoskeletal conditions

Joletta Belton, Hollie Birkinshaw & Tamar Pincus

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, Volume 30, Issue 53, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-022-00466-w

Summary

Patient Perspectives on Participation in Cognitive Functional Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain

Samantha Bunzli, Sarah McEvoy, Wim Dankaerts, Peter O'Sullivan, Kieran O'Sullivan

Physical Therapy, Volume 96, Issue 9, 1 September 2016, Pages 1397–1407, https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140570

Summary

Methods

- 4 participants who achieved a large improvement (>60%)

- 3 participants who did not change (<30% improvement)

- 2 participants who improved a little (~50%)

- 2 participants were recruited who experienced significant reductions in pain-related fear resulting in them no longer meeting the criteria for 'high fear' after CFT

- 3 participants were recruited who experienced improvements in pain-related fear but still met the criteria for 'high fear' after CFT

Two themes emerged from the interviews:

Theme 1 - Changing Pain Beliefs

- Participant entered the study with biomedical beliefs.

- Acceptance of a biopsychosocial model differentiated large improvers from small improvers.

- Therapeutic alliance seemed to differentiate large improvers from non-improvers and be an attribute that was associated with successfully changing pre-existing beliefs.

- Body awareness was shifted in people who improved, affecting their perception of themselves both physically and mentally, while those who did not improve were not empowered by this experience.

- Experiencing pain control resulted from improved body awareness in people who improved, in contrast, those who did not improve did not experience pain control through improved body awareness.

Theme 2 - Achieving Independence

- Problem solving and self-efficacy facilitated patients perceptions of control of their problem and future pain experiences, and large improvements in either disability and pain self-efficacy

- Concerns about the cause of pain, and their ability to cope, remained in those who improved a little and those who did not improve at all.

- Fear about new pain episodes reduced substantially in large improvers due to an understanding about the cause of their pain and ability to self manage symptoms, while those who improved a little or did not improve at all remained fearful about movement, pain intensity and their ability to control flareups.

- Stress coping improved significantly in large improvers where they acknowledged the effect of lifestyle and stress on the pain experience. Those who improved a little or did not improve at all found it challenging to manage stress or did not acknowledge stress as being related to their pain experience.

- Normality was described by large improvers where they were no longer defined by their pain experience and returned to normal activities. In small improvers, although they were coping better, their pain relapses reminded them they were not 'normal'.

Physiotherapists report improved understanding of and attitude toward the cognitive, psychological and social dimensions of chronic low back pain after Cognitive Functional Therapy training: a qualitative study

Aoife Synnott, Mary O’Keeffe, Samantha Bunzli, Wim Dankaerts, Peter O'Sullivan, Katie Robinson, Kieran O'Sullivan.

Journal of Physiotherapy, Volume 62, Issue 4, October 2016, Pages 215-221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2016.08.002

Summary

Methods

Four themes emerged from the interviews:

Theme 1

Theme 2

Theme 3

Theme 4

Physiotherapists’ validating and invalidating communication before and after participating in brief Cognitive Functional Therapy training. Test of concept study

Riikka Holopainen, Mikko Lausmaa, Sara Edlund, Johan Carstens-Söderstrand, Jaro Karppinen, Peter O’Sullivan & Steven J. Linton

European Journal of Physiotherapy, Volume 25, Issue 2, 23 September 2021, Pages 73-79, https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2021.1967446

Riikka Holopainen, Mikko Lausmaa, Sara Edlund, Johan Carstens-Söderstrand, Jaro Karppinen, Peter O’Sullivan & Steven J. Linton

European Journal of Physiotherapy, Volume 25, Issue 2, 23 September 2021, Pages 73-79, https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2021.1967446

Summary

Methods

Results

Cognitive Functional Therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial

Peter Kent, Terry Haines, Peter O'Sullivan, Anne Smith, Amity Campbell, Robert Schutze, Stephanie Attwell, JP Caneiro, Robert Laird, Kieran O'Sullivan, Alison McGregor, Jan Hartvigsen, Den-Ching A Lee, Alistair Vickery, Mark Hancock. The Lancet, Volume 401, Issue 10391, 3 June 2023, Pages 1866-1877, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00441-5

Peter Kent, Terry Haines, Peter O'Sullivan, Anne Smith, Amity Campbell, Robert Schutze, Stephanie Attwell, JP Caneiro, Robert Laird, Kieran O'Sullivan, Alison McGregor, Jan Hartvigsen, Den-Ching A Lee, Alistair Vickery, Mark Hancock. The Lancet, Volume 401, Issue 10391, 3 June 2023, Pages 1866-1877, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00441-5

Summary

Methods

- People were able to seek care as usual with no restrictions.

- Sensors were placed on the participant to assist blinding and provide movement information for the trial.

- The sensor data was not accessible by either the patient or physiotherapist.

- Sensors were placed on the participant to provide personalised feedback on movement and posture, as directed by their physiotherapist.

- Data was accessible by the patient and physiotherapist.

Results

What do the results mean?

It's time for a change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain.

Peter O'Sullivan. British Journal of Sports Medicine, Volume 46, Issue 4, 1 March 2012, Pages 224-227, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.081638

Peter O'Sullivan. British Journal of Sports Medicine, Volume 46, Issue 4, 1 March 2012, Pages 224-227, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.081638

Summary

- Only a small percentage of back pain cases are due to a clear structural issue.

- Factors like stress, fear of movement, and negative beliefs about pain can make symptoms worse.

- Many common treatments, such as muscle strengthening exercises and spinal injections, don’t offer better results than general exercise or lifestyle changes.

- Over-focusing on "stability" and "perfect posture" can actually make pain worse by increasing fear and tension.

A New Approach: Treating the Whole Person

- Successful treatment focuses on helping people move confidently rather than just strengthening muscles.

- Cognitive-behavioral approaches that address fear, stress, and lifestyle habits show better results in reducing pain and disability.

- Patients need reassurance that movement is safe and that their pain is manageable.

Encouraging Self-Management and Active Lifestyles

- Rather than avoiding activities, patients should gradually return to normal movement and exercise.

- Addressing emotional and psychological factors—like reducing fear and stress—can improve pain management.

- A personalised, multidimensional approach is more effective than one-size-fits-all treatments.

From protection to non-protection: A mixed methods study investigating movement, posture and recovery from disabling low back pain

Kevin Wernli, Anne Smith, Fiona Coll, Amity Campbell, Peter Kent, Peter O'Sullivan. British Journal of Sports Medicine, Volume 26, 12 August 2022, Pages 2097-2119, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.2022

Kevin Wernli, Anne Smith, Fiona Coll, Amity Campbell, Peter Kent, Peter O'Sullivan. British Journal of Sports Medicine, Volume 26, 12 August 2022, Pages 2097-2119, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.2022

Summary

- Understand how people with persistent low back pain think about their movement and posture before and after treatment.

- Measure how changes in movement, posture, and psychological factors relate to pain recovery.

Research Methodology

- Help them understand their pain and reduce fear of movement.

- Guide them in gradually moving more freely and confidently.

- Address psychological and lifestyle factors contributing to their pain.

How Was Recovery Measured?

- Interviews before and after treatment – to understand how participants thought and felt about their pain and movement.

- Movement and posture analysis – using wearable sensors to track spinal movement, muscle activity, and posture.

- Questionnaires – measuring pain levels, activity limitations, and psychological factors such as fear of movement.

Key Findings

- Stiff, tense, or locked up

- Fragile or at risk of further injury

- In constant need of protection through careful movement and posture

- Many avoided certain movements or held their muscles tight, believing this would prevent further pain. Some reported that healthcare advice and societal messages reinforced these fears.

- As participants progressed through therapy, they gradually became less protective. Their recovery followed three different pathways:

- Some still needed to focus on moving differently ("Conscious Non-Protection")

- These participants had to actively remind themselves to relax and move more freely.

- Some began to move naturally and without fear ("Nonconscious Non-Protection")

- These individuals forgot about their pain and returned to normal movement without effort.

- A few remained protective despite treatment.

- One participant continued to brace and avoid movement, suggesting that some people need more time or a different approach.

3. Improved Movement and Less Pain

- Less pain and stiffness

- Increased spinal movement and flexibility

- More confidence in daily activities

- Reduced fear of movement

Movement sensors showed that as pain improved, people:

- Moved more quickly and smoothly

- Stopped bracing their muscles unnecessarily

- Adopted more relaxed postures

What Does This Mean for People with Back Pain?

- The main takeaway from this study is that over-protecting the back can sometimes make pain worse. Rather than focusing on rigid posture and avoiding movement, people with chronic low back pain may benefit from:

- Gradually moving more freely and confidently

- Challenging their fear of movement

- Recognising that their back is not as fragile as they may think

- Working with a physiotherapist trained in Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) can help people shift from fearful, protective movement to more natural, relaxed movement—leading to pain relief and improved function.

A Prospective Qualitative Inquiry of Patient Experiences of Cognitive Functional Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain During the RESTORE Trial

Nardia-Rose Klem, Peter O’Sullivan, Anne Smith, and Robert Schütze. Qualitative Health Research, 9 September 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323241268777

Nardia-Rose Klem, Peter O’Sullivan, Anne Smith, and Robert Schütze. Qualitative Health Research, 9 September 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323241268777

Summary

Clinicians should:

- Provide clear, personalised explanations to help patients make sense of their pain.

- Offer graded exposure to feared movements, ensuring patients feel supported and confident.

- Recognise that not all patients progress at the same pace; some may need extended or additional interventions to address persistent challenges.

- Use pain flares as an opportunity for education and skill-building to enhance self-management.

What Influences Patient-Therapist Interactions in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy? Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis

Mary O'Keeffe, Paul Cullinane, John Hurley, Irene Leahy, Samantha Bunzli, Peter B. O'Sullivan, Kieran O'Sullivan. Physical Therapy, 1 May 2016, Volume 96, Issue 5, Pages 609-622, https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20150240

Mary O'Keeffe, Paul Cullinane, John Hurley, Irene Leahy, Samantha Bunzli, Peter B. O'Sullivan, Kieran O'Sullivan. Physical Therapy, 1 May 2016, Volume 96, Issue 5, Pages 609-622, https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20150240

Summary

- Listen actively and let them share their story.

- Show empathy—understanding how pain affects their daily life.

- Be friendly and approachable, making them feel comfortable.

- Encourage and motivate them throughout treatment.

- Communicate with confidence, so patients feel reassured.

- Good communication helps build trust, making the patient more likely to stick with treatment and see better results.

- Had strong expertise and practical skills.

- Explained things in simple terms (not complicated medical jargon).

- Taught them about their condition so they could manage it better at home.

- When patients understood what was happening in their body and why certain treatments were used, they felt more in control of their recovery.

- Tailored to their specific needs, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

- Based on their opinions and preferences, rather than just following a standard plan.

- This made them feel valued and encouraged them to take an active role in their recovery.

- They were given enough time to discuss their issues and weren’t rushed.

- Therapists were flexible with appointments and follow-ups.

- On the other hand, long wait times and limited access to therapists made some patients feel frustrated and disengaged.

- Ask questions and make sure you understand your treatment.

- Share your concerns—a good therapist will listen and adjust care to suit you.

- Look for a therapist who makes you feel heard, respected, and involved in your recovery.

Patients with worse disability respond best to cognitive functional therapy for chronic low back pain: a pre-planned secondary analysis of a randomised trial

Mark Hancock , Anne Smith , Peter O’Sullivan , Robert Schütze , JP Caneiro, Jan Hartvigsen, Kieran O’Sullivan, Alison McGregor, Terry Haines, Alistair Vickery, Amity Campbell, Peter Kent. Journal of Physiotherapy, 16 October 2024, Volume 70, Issue 4, Pages 294-301, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2024.08.005

Mark Hancock , Anne Smith , Peter O’Sullivan , Robert Schütze , JP Caneiro, Jan Hartvigsen, Kieran O’Sullivan, Alison McGregor, Terry Haines, Alistair Vickery, Amity Campbell, Peter Kent. Journal of Physiotherapy, 16 October 2024, Volume 70, Issue 4, Pages 294-301, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2024.08.005

Summary

Study Design:

The RESTORE trial included 492 adults with CLBP for over three months, with moderate to severe pain-related activity limitation.

Participants were randomised into groups receiving CFT (with or without biofeedback) or usual care.The primary outcome was activity limitation, measured using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), assessed over 52 weeks.

Key Results:

Other Factors: Cognitive flexibility may influence short-term benefits of CFT, but this effect was not sustained long-term. Pain intensity, self-efficacy, and catastrophising did not significantly affect the outcomes.

Overall Effectiveness: CFT demonstrated consistent benefits across the spectrum of disability, with the strongest effects in patients with the most severe baseline activity limitations.

Clinical Implications:

Targeting High-Need Patients: CFT is particularly effective for patients with severe disability, who often experience the greatest health burden and are the most challenging to treat.

Universal Benefit: While most effective in highly disabled individuals, CFT remains beneficial for patients with lower levels of disability.

Efficient Resource Use: If access to CFT is limited, prioritising patients with severe disability may maximise clinical impact.

Conclusion:

CFT provides a robust and effective treatment option for CLBP, especially in individuals with greater baseline disability. This study highlights the importance of tailoring interventions based on patient characteristics to optimise outcomes.

The "future" pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

Steven J Linton, Peter B O'Sullivan, Hedvig E Zetterberg, Johan W S Vlaeyen. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 8 August 2024, Volume 24, Issue 1, Pages 294-301, https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2024-0017

Steven J Linton, Peter B O'Sullivan, Hedvig E Zetterberg, Johan W S Vlaeyen. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 8 August 2024, Volume 24, Issue 1, Pages 294-301, https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2024-0017

Summary

- Helping patients understand their pain in a way that makes sense to them.

- Teaching strategies to manage pain better, including relaxation techniques, movement retraining, and mindset shifts.

- Encouraging patients to gradually return to daily activities rather than avoiding movement out of fear.

- Using a personalized approach—what works for one person may not work for another.

- Listening to patients and validating their experiences.

- Explaining pain in a way that makes sense without using confusing medical terms.

- Helping patients feel understood and supported.

Understanding Pain Science

- Knowing how pain works, including the role of the nervous system, emotions, and behaviors.

- Understanding that pain isn’t always caused by tissue damage—it can be influenced by stress, fear, and past experiences.

Behavior Change Techniques

- Helping patients gradually return to activities they have been avoiding due to fear of pain.

- Teaching relaxation techniques to reduce muscle tension and stress-related pain.

- Encouraging self-management, so patients feel more in control of their pain.

Individualised Treatment Planning

- Creating a treatment plan based on each patient’s goals, fears, and daily challenges rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach.

- Using psychological strategies (like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) to help patients challenge negative thoughts about pain.

Mechanisms of change in cognitive functional therapy: A longitudinal mediation analysis of the RESTORE clinical trial for disabling chronic low back pain

Robert Schütze, Bernard Liew, JP Caneiro, Peter O’Sullivan, Peter Kent, Mark Hancock, Jan Hartvigsen, Kieran O’Sullivan, Alison McGregor, Amity Campbell, Stephanie Attwell, Anne Smith. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 3 September 2025, Volume 193, Article 104853, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2025.104853

Robert Schütze, Bernard Liew, JP Caneiro, Peter O’Sullivan, Peter Kent, Mark Hancock, Jan Hartvigsen, Kieran O’Sullivan, Alison McGregor, Amity Campbell, Stephanie Attwell, Anne Smith. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 3 September 2025, Volume 193, Article 104853, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2025.104853

Background

Study Design

- Trial: RESTORE RCT (n = 492; CFT = 327, usual care = 165)

- Analysis: Longitudinal mediation using counterfactual framework

- Mediators tested: Pain self-efficacy, fear of movement, catastrophising, and pain intensity Outcomes: Disability (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire) and pain intensity (0–10 NRS)

- Follow-up: 13 weeks (post-treatment) and 52 weeks

Key Findings

- CFT produced greater early improvements in self-efficacy, fear, catastrophising, and pain intensity compared to usual care.

- These changes mediated long-term improvements in both disability and pain.

- Mediators explained:

- 47% of disability improvements at 13 weeks, 61% at 52 weeks

- 43% of pain improvements at 13 weeks, 62% at 52 weeks

- Self-efficacy, fear, and catastrophising consistently mediated outcomes; pain intensity also mediated disability.

Clinical Implications

- CFT’s effects are strongly explained by targeting unhelpful pain beliefs and behaviours (fear, catastrophising, low confidence) alongside graded movement exposure and lifestyle change.

- These mechanisms are common to effective biopsychosocial pain treatments, but CFT appears to activate them robustly and durably.

- Clinicians should focus on:

- Building patient confidence to move (self-efficacy)

- Helping patients make sense of pain as non-threatening

- Supporting graded exposure to feared/avoided movements

- Encouraging lifestyle and activity re-engagement

Takeaway for Practice

Cognitive Functional Therapy:

An Integrated Behavioral Approach for the Targeted Management of Disabling Low Back Pain

Summary

Section 1 - "Multidimensional Factors Associated with Disabling LBP"

Section 2 - "Cognitive Functional Therapy: Assessment and Treatment"

Section 3 - "Skills Required to Implement CFT"

-

Communication skills to sensitively explore how people think and feel about their problem, build strong therapeutic alliance, enhance self-efficacy and promote behaviour change.

-

Strong clinical reasoning skills to triage and synthesize multidimensional information.

-

Observation skills are required to analyse functional and safety behaviours.

-

Hands-on feedback and movement facilitation skills are needed to guide behavioural experiments and teach new behaviours.

-

Clinicians need to have confidence to discourage safety behaviours, and to intrinsically recognise that pain is more strongly related to multidimensional factors, rather than damage, that the spine is strong and movement is helpful.

From Fear to Safety: A Roadmap to Recovery From Musculoskeletal Pain

Summary

Fear learning

- Identity (what is this pain? e.g. structure)

- Cause (what caused this pain? e.g. bending)

- Consequences (what are the consequences of this pain? e.g. disability)

- Timeline (for how long will this pain last?)

- Cure/controllability (can this pain be cured or controlled?)

Safety-learning

- Screen

- Interview

- Examine

- Expose with Control

- Make Sense of Pain

- Integrate into daily life

- Provide an flare-up plan

- Refer if co-care is required

CFT to promote safety-learning

B) Core elements of Cognitive Functional Therapy as a vehicle to promote safety learning. The experience may confirm or violate the original schema. Confirmation of pain as a threatening experience (i.e. learning does not occur) leads to the reinforcement of the person’s fear response. Violation of pain as a threatening experience (i.e. learning of safety occurs) can powerfully disconfirm fear-avoidance beliefs while reinforcing that valued activities can be safely confronted when performed without safety behaviors and reduced pain vigilance. This leads to an update of the person’s response that promotes generalisation of safety.

C) Person’s common-sense response to an experience interpreted as safe (Safety schema).

D) Response to a pain flare, which may reinforce fear or safety learning. This is a crucial learning opportunity that influences a person’s process to recovery.

Evထlve Pain Care Academy recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as Australia’s first peoples. We acknowledge the unique connection that First Nations peoples have to land, waters and the environment. We extend this recognition and respect to First Nations peoples and communities around the world.

The information provided is general information only.

Clinicians should use their own professional judgement in determining the best care for each patient.

People who have pain should consult with their healthcare team before acting on any information.

The content does not create any formal clinical or doctor-patient relationship.

EVOOLVE, its directors, employees, and affiliates shall not be liable for any damages, losses, or adverse outcomes arising from the use of this information.

This information is provided ‘as is’ without any warranties, express or implied.

EVOOLVE reserves the right to update or modify this information and these disclaimers at any time without notice.

These disclaimers are governed by the laws of Western Australia.

© Copyright 2026

Evoolve Pain Care Academy Pty Ltd (ABN 13672998168)

215 Nicholson Rd, Shenton Park,

Western Australia 6008

Dr Jay-Shian Tan

Australia

Evထlve creative works, web design, social media

Jay is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy educator and clinician. He is passionate helping clinicians translate evidence into practice through personalised face-to-face and online mentoring. He has extensive experience as an undergraduate and postgraduate educator in the university sector and provides professional development and mentoring for graduate clinicians in their practice.

- PhD | MSc Musc. Physio | BSc Physiotherapy

- Titled Member of the Australian College of Physiotherapy

- Clinical Consultant at Flex.Physio

- Clinical educator

Dr Riika Holopainen

Finland

Evထlve creative works

Riikka is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy researcher and educator. She is pasionate about identifying best practice rehabilitation and enabling ways for clinicians to deliver that care.

- Physiotherapist

- PhD | PT

- Consultant at MoveDoc

- Clinical educator

Dr Ian Cowell

United Kingdom

Evထlve creative works and Certified CFT trainer

Ian is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy educator and clinician with a particular interest in the management of persistent musculoskeletal pain disorders. His research focus is how person-centred communication is enacted in physiotherapist-patient interactions.

- PhD | MSc Musc. Physio

- Director and clinician - Brook Physio

- Clinicial educator

Prof Peter O'Sullivan

Australia

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer,

creative works co-lead

Pete is internationally recognised as a leading clinician, researcher and educator in musculoskeletal pain disorders. Over the past 20 years, Pete and his team have developed a novel management approach for people with disabling low back pain – called 'Cognitive Functional Therapy'. Pete's passion is to bridge the gap between research and practice – in order to empower researchers, educators and clinicians in the provision of person-centred care for people in pain.

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist*

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- John Curtin Distinguished Professor Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2005)

Dr JP Caneiro

Australia

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer,

creative works co-lead

JP is an emerging leader in the field of chronic pain, particularly the management of back pain and osteoarthritis. He is passionate about mentoring clinicians to ensure the highest level of care is provided in clinical practice. Born and raised in Brazil, JP also speaks Portuguese fluently and is committed to affordable translatable knowledge that is accessible to clinicians regardless of country.

- Specialist Sport Physiotherapist*

- Titled Pain Physiotherapist

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- PhD | MSc Musc. & Sports Physio

- Adjunct Clinical Senior Researcher - Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2013)

Dr Peter Kent

Peter is a musculoskeletal pain researcher and was the lead researcher on the RESTORE trial for people with low back pain. For more than 20 years he practiced as a Physiotherapist & Chiropractor.

- Clinical Epidemiologist

- PhD | Grad.Dip.Manip.Physio | B.App.Sc.(Physio) | B.App.Sc (Chiro)

- Mindfullness teacher

Assoc Prof Kjartan Vibe Fersum

Norway

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- PhD | MSc Musculoskeletal Physio | BSc Physio

- Director and Clinician at Health In the Center (Bergen, Norway)

- Associate Professor at University of Bergen (UIB)

- Lecturer for Musculoskeletal Masters programme (UIB)

- Clinical educator

Assoc Prof Wim Dankaerts

Belgium

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

Wim is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy clinician, researcher and educator with a particular interest in the integration of a multi-dimensional clinical reasoning process and person-centred communication to enhance self-management in patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain disorders.

- Professor of Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy - University of Leuven, Belgium

- PhD – PT – MT

- Clinical Director and Clinician - @PVMT, Tienen, Belgium

- Clinical educator

Kasper Ussing

Denmark

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- Master of Manipulative Therapy (Curtin University)

- Co-owner Spine & Mind Fysio

- Coordinator of Unit for Cross Sectional Cooperation (spinal care) - Spine Centre of Southern Denmark

Gurpreet Singh

United Kingdom

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- BSc | M Research

- Clinical educator

- Guest lecturer University of Coventry and University of Leicester

Dr Chris Newton

United Kingdom

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Consultant Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist and clinical academic at University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire

- PhD | MSc Advanced Musculoskeletal Practice

Irene Stegemejer

Denmark

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- Multidisciplinary Pain Centre, Odense University Hospital

- Co-owner Spine & Mind Fysio

Jannick Johansen

Denmark

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- Master in Fitness and Exercise (University of Southern Denmark)

- Co-owner Spine & Mind Fysio

- Bachelor in Physiotherapy, Physiotherapy School in Odense

Infographic

Why does my back hurt?

please get in touch.

Infographic

The best way to care for your back pain

please get in touch.

Just a reminder...

Infographic

Becoming Confidently Competent

please get in touch.

Infographic

From despair to living again

please get in touch.

Professor Peter O'Sullivan

AUSTRALIA

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer, creative works co-lead

Pete is internationally recognised as a leading clinician, researcher and educator in musculoskeletal pain disorders. Over the past 20 years, Pete and his team have developed a novel management approach for people with disabling low back pain – called 'Cognitive Functional Therapy'. Pete's passion is to bridge the gap between research and practice – in order to empower researchers, educators and clinicians in the provision of person-centred care for people in pain.

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist*

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- John Curtin Distinguished Professor Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2005)

Dr JP Caneiro

AUSTRALIA

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer, creative works co-lead

JP is an emerging leader in the field of chronic pain, particularly the management of back pain and osteoarthritis. He is passionate about mentoring clinicians to ensure the highest level of care is provided in clinical practice. Born and raised in Brazil, JP also speaks Portuguese fluently and is committed to affordable translatable knowledge that is accessible to clinicians regardless of country.

- Specialist Sport Physiotherapist*

- Titled Pain Physiotherapist

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- PhD | MSc Musc. & Sports Physio

- Adjunct Clinical Senior Researcher - Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2013)