Resources

for clinicians working with people living

with low back pain

Videos

stories of recovery

Infographics

Literature

General Information

The information provided is based on the latest scientific evidence but is for general educational purposes only. It should not be used as a substitute for your clinical judgement or professional advice.

Patient Assessment

Clinicians must use their own qualifications and scope of practice to determine whether a patient’s back pain is related to ‘specific’ pathology. Where in doubt, refer patients to a suitably qualified health professional.

No Clinician-Patient Relationship

The information provided does not create a clinician-patient or formal clinical relationship.

Limitation of Liability

EVOOLVE, its directors, employees, and affiliates shall not be liable for any damages, losses, or adverse outcomes arising from the use of this information.

As Is

This information is provided ‘as is’ without any warranties, express or implied.

Updates

EVOOLVE reserves the right to update or modify this information and these disclaimers at any time without notice.

Governing Law

These disclaimers are governed by the laws of Western Australia.

There are different kinds of low back pain - 'non-specific' and 'specific'.

Non-specific low back pain

This type of back pain is associated with sensitivity of the spinal structures that is attributable to a variety of different factors. These may include: mechanical strain, muscle tension, poor sleep, being run down, tired, stressed, tense, sad, inactive or over-active, as well as the health of the spinal structures (e.g. disc degeneration, arthritis, disc bulges with no nerve compression).

These factors vary for each person thereby influencing their level of pain and disability.

Specific low back pain

This may include low back pain related to cancer, infection, fracture or an inflammatory process, such as spondyloarthropathy, or internal organ pathology. While these conditions are rare (about 1% of people) they require urgent medical attention.

About 5% of people have nerve compression resulting in a loss of power and sensation in the lower limb. In rare cases, this may also affect the function of the bowel or bladder. This requires urgent medical attention.

A clinician’s ability to determine whether a patient's back pain is related to 'specific' pathology is dependent on their qualification and scope of practice. For example, a medical doctor is trained to do this and in most parts of the world so is a physiotherapist. Anyone who works with people with low back pain and who is not qualified to make this assessment, needs to refer their patients to a qualified health professional for that assessment.

The following videos and infographics relate to people who have non-specific low back pain.

Videos

Separating Fact from Fiction

-

What the research says

-

Problems with MRI

-

Things clinicians say that scare patients

-

Unhelpful behaviours and beliefs can drive pain and disability

-

Pain is multidimensional

-

Fear drives behaviour

Hope for change

-

From the Feel Better Live More podcast

-

Back facts everyone should know

-

Learn about what is healthy for your back

-

Personal pain stories

-

Lets help people develop hope

Stories of Recovery

Hear from people who have had disabling low back pain.

Learn how they restored trust in their back and built confidence to take control of their life.

- Firefighter with active hobbies

- "My doctor said I have the back of a 60yo"

- Avoiding activity and good posture didn't help

- Lost hope

- Retired grandmother

- Tried many interventions with many clinicians and was told to give up being active

- MRI - bulging discs and degeneration

- "I was so stiff, so tense and so frightened...I became less confident with everything, and depressed"

- Australian Aboriginal man and basketballer

- Couldn't exercise for his mental health

- "I couldn't contribute at home or work"

- After side-effects from medication, underwent surgery, but the pain remained

- CFO and triathlete

- Quit job and stopped training

- Surgeon couldn't see anything wrong on MRI, in fact it was 'better' than most

- "I was broken and in a dark place"

- Mum and nurse

- At 20 was told - "you'll be in a wheelchair by 40"

- Chronic fatigue, disempowered, confused, depressed

- Avoided playing with kids and living in a state of fear

- Quit manual job and football

- Was told "you have the back of a 70 year old"

- Felt that back was "in pieces"

- Very guarded and protective

- Widespread low back to neck pain after crashing bicycle

- Post-traumatic stress response

- Ongoing pain despite going to doctors, physio, Pilates, acupuncture and trying stand up desk and different chairs

- Was told - "you need to brace your core"

- School principle and rugby player

- Received an MRI resulting in a belief that he needed to protect his back

- Performed lots of 'core' exercise

- Very guarded and protective

Infographics

Co-designed by researchers and clinicians in partnership with people living with back pain, these infographics summarise the evidence about the most common questions asked by people with low back pain.

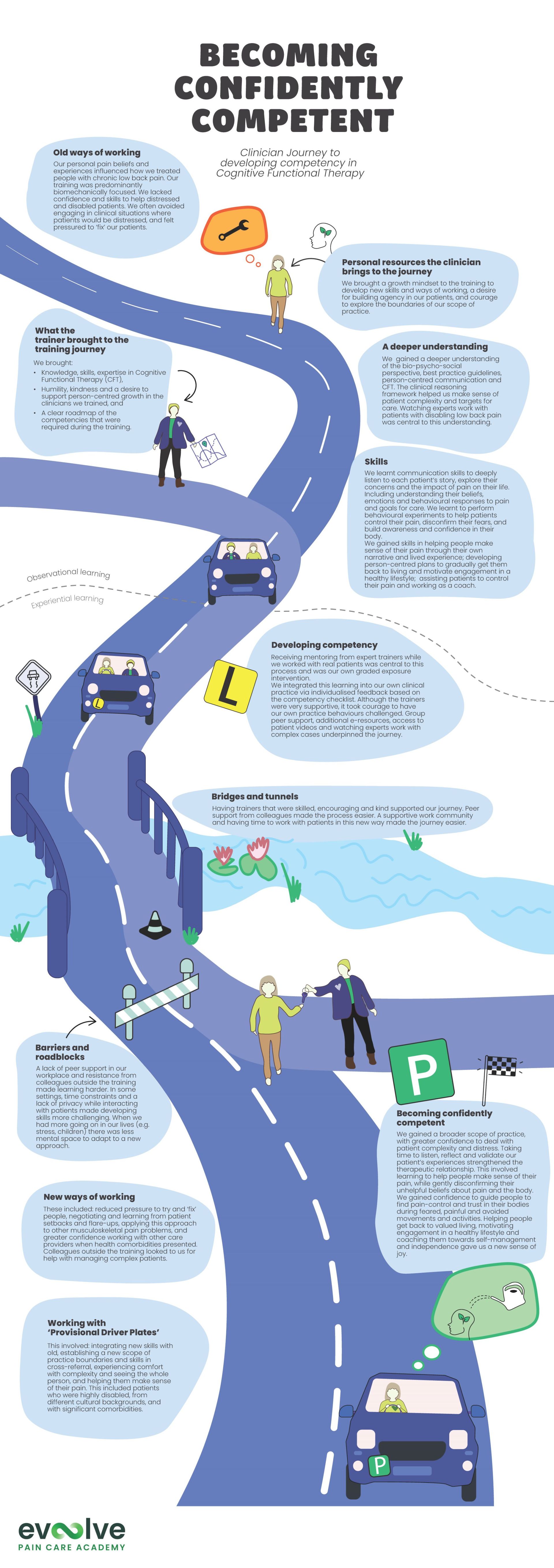

"Becoming Confidently Competent" outlines the clinician training journey to becoming a certified Cognitive Functional Therapy practitioner.

Literature

Best Practice Guidelines for Musculoskeletal Pain

What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review

British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878

This paper reviewed high-quality guidelines for managing common musculoskeletal pain conditions such as back, neck, knee, hip, and shoulder pain. It identified 11 key recommendations to ensure patients receive the best possible care.

The 11 key recommendations:

Identify serious pathology (e.g., fractures, malignancies, infections, cauda equina syndrome) before initiating routine musculoskeletal pain management.

Avoid routine imaging unless there are red flag indications, persistent symptoms despite conservative management, or imaging is expected to influence treatment decisions.

Assess movement, strength, neurological function, and pain responses to classify the condition appropriately and guide treatment planning.

Use standardised outcome measures to track functional improvement, pain levels, and overall patient well-being over time.

Provide clear, evidence-based education to enhance self-management, address misconceptions, and improve adherence to active treatments.

If utilised, manual therapy (e.g., spinal manipulation, mobilisation, soft tissue techniques) should be integrated with active rehabilitation approaches.

Unless there is a clear indication for surgery, emphasise conservative interventions such as exercise, physical therapy, and pain education before considering surgical referral.

Support strategies that promote work engagement or return to activity, including workplace modifications, graded exposure, and vocational rehabilitation when needed.

Identifying Serious Spinal Pathology

International Framework for Red Flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies

Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2020.9971

The framework provides a clear clinical reasoning pathway for:

- Determining the level of clinical concern

- Clinical decision making

- Considering appropriate pathways for urgent referral

As there are total of 163 red flags that have been identified across the literature we recommend clinicians become familiar with red flags described within Finucane et al. (2020), and the Australian Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard Full Publication (pages 19 and 29).

Decision Tool for Early Identification of Serious Spinal Pathology

Press (+) to expand each section

1. Determine the level of concern

2. Decide the clinical action

3. Consider pathway for referral

Cognitive Functional Therapy and other

Patient-centred Care Research

Below is a collection of open access academic research.

Click your paper of interest to be taken to a clinical summary and link to the full paper.

Cognitive Functional Therapy:

Peter O'Sullivan et al. 2018

The Australian Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard

International Low Back Pain Clinical Guidelines

-

Screening for serious pathology / red flags

-

Appropriate referral for medical imaging (i.e. eliminating routine referrals)

-

Psychological therapy (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy)

-

Provide patient education

-

Movement and exercise

Conducting a Patient-Centred Consultation

Patient-centered consultations for persons with musculoskeletal conditions

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, Volume 30, Issue 53, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-022-00466-w

Abstract:

Consultations between practitioners and patients are more than a hypothesis-chasing exploration, especially when uncertainty about etiology and prognosis are high. In this article we describe a single individual's account of their lived experience of pain and long journey of consultations. This personal account includes challenges as well as opportunities, and ultimately led to self-awareness, clarity, and living well with pain. We follow each section of this narrative with a short description of the emerging scientific evidence informing on specific aspects of the consultation. Using this novel structure, we portray a framework for understanding consultations for persistent musculoskeletal pain from a position of patient-centered research to inform practice.

Adapted from "Patient‑centered consultations for persons with musculoskeletal conditions. By Belton et al., 2022, Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 30(53). (https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-022-00466-w). Copyright 2022 by the authors (Creative Commons).

Effective Data Collection

-

Let patients tell their narrative

-

Explore impact of pain on life

-

Elicit emotions and beliefs

-

Ask open ended questions

-

Allow patients to tell their story

-

Check if you understand what matters to them

-

Check if you need to know anything else

-

Try to avoid chasing hypotheses while people are talking

-

Explore the whole person. Don't avoid emotions, concerns and problems that are beyond your perceived scope

-

Listen, avoid interrupting

-

Respond empathetically

-

Show that you are attentive

-

Indicate that it is important

-

Ask open ended questions

-

Allow patients to tell their story

-

Check if you understand what matters to them

-

Recognise suffering and distress

-

Indicate that you believe all aspects of the narrative

-

Indicate that distress is understandable

-

Be clear and explicit about the fact that you believe the patient

-

Acknowledge the pain and suffering

-

Explicitly indicate that distress is completely normal under the circumstances

-

Where possible, describe possible causes

-

Discuss likely prognosis

-

Discuss / agree about possible interventions

-

Discuss prognosis, treatment options and likely obstacles

-

Use simple language and avoid jargon

-

Make sure the conversation flows both ways

-

Discuss prognosis, treatment options and likely obstacles

Avoid Generic Reassurance

- Seen many clinicians

- Trialed many interventions

- A long history of pain and suffering

-

Avoid telling patients that everything will be alright unless you really know this is the case

-

Recognise that telling patients nothing is wrong is not always reassuring

Share

Evထlve Pain Care Academy recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as Australia’s first peoples. We acknowledge the unique connection that First Nations peoples have to land, waters and the environment. We extend this recognition and respect to First Nations peoples and communities around the world.

The information provided is general information only.

Clinicians should use their own professional judgement in determining the best care for each patient.

People who have pain should consult with their healthcare team before acting on any information.

The content does not create any formal clinical or doctor-patient relationship.

EVOOLVE, its directors, employees, and affiliates shall not be liable for any damages, losses, or adverse outcomes arising from the use of this information.

This information is provided ‘as is’ without any warranties, express or implied.

EVOOLVE reserves the right to update or modify this information and these disclaimers at any time without notice.

These disclaimers are governed by the laws of Western Australia.

© Copyright 2026

Evoolve Pain Care Academy Pty Ltd (ABN 13672998168)

215 Nicholson Rd, Shenton Park,

Western Australia 6008

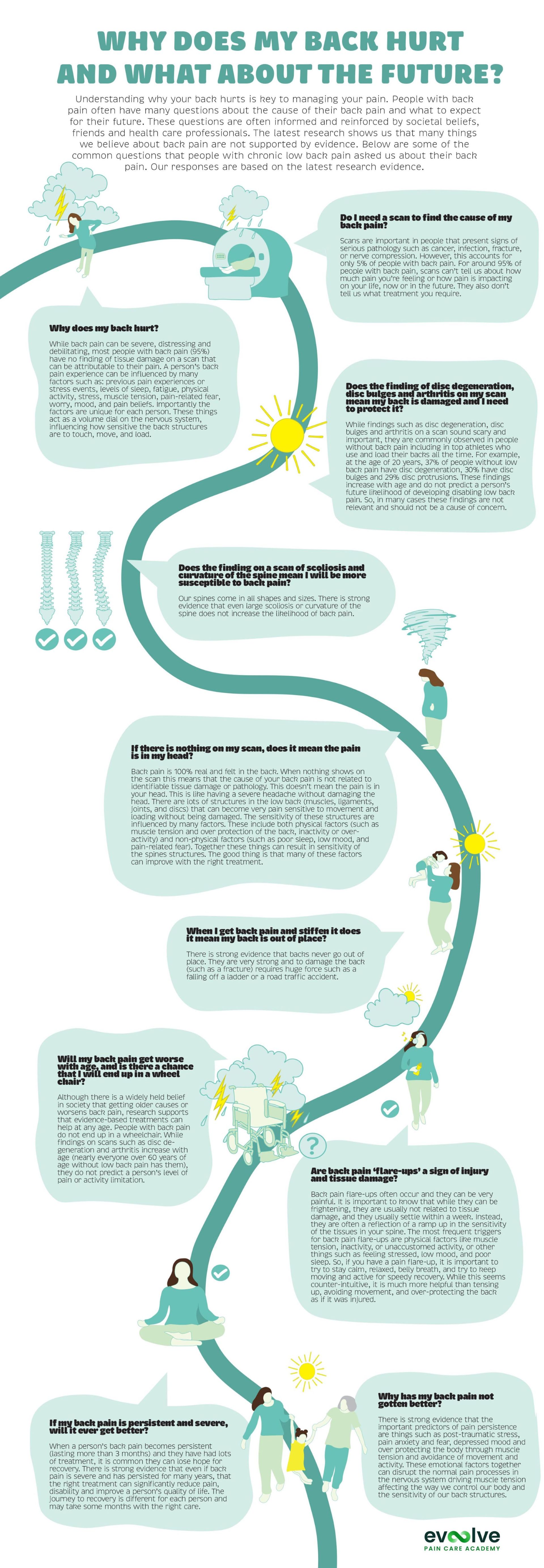

Infographic

Why does my back hurt?

please get in touch.

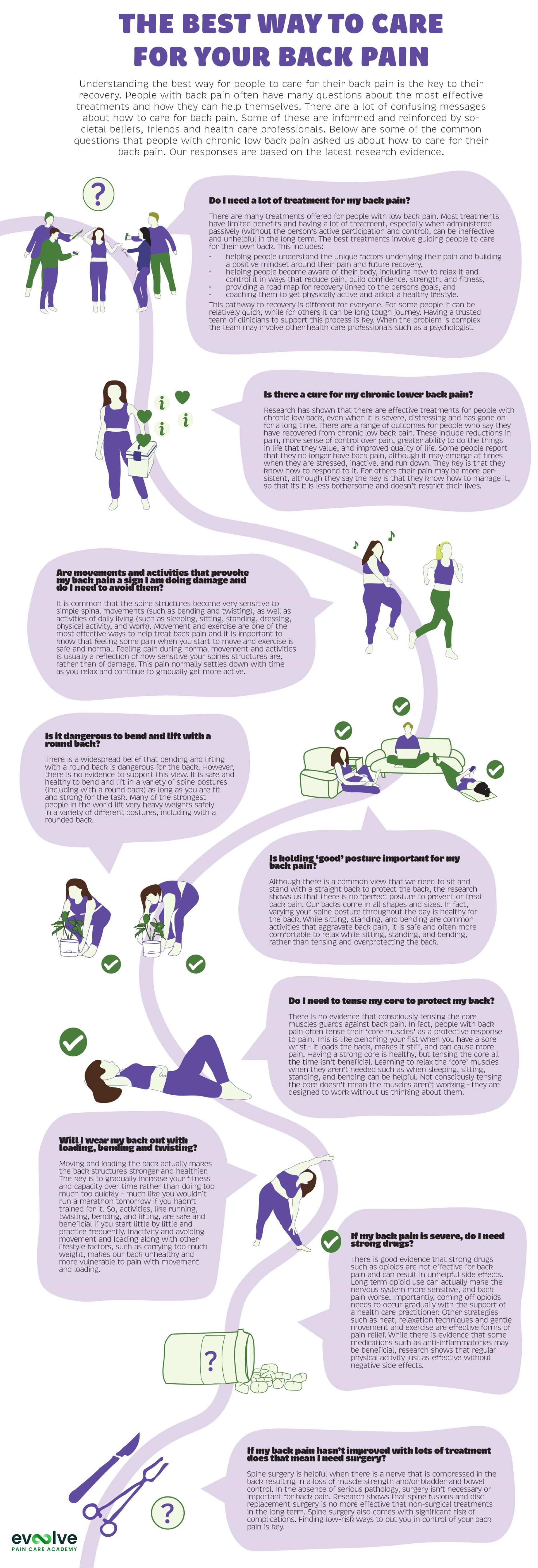

Infographic

The best way to care for your back pain

please get in touch.

Infographic

Becoming Confidently Competent

please get in touch.

Dr Jay-Shian Tan

Australia

Evထlve creative works, web design, social media

Jay is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy educator and clinician. He is passionate helping clinicians translate evidence into practice through personalised face-to-face and online mentoring. He has extensive experience as an undergraduate and postgraduate educator in the university sector and provides professional development and mentoring for graduate clinicians in their practice.

- PhD | MSc Musc. Physio | BSc Physiotherapy

- Titled Member of the Australian College of Physiotherapy

- Clinical Consultant at Flex.Physio

- Clinical educator

Dr Riika Holopainen

Finland

Evထlve creative works

Riikka is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy researcher and educator. She is pasionate about identifying best practice rehabilitation and enabling ways for clinicians to deliver that care.

- Physiotherapist

- PhD | PT

- Consultant at MoveDoc

- Clinical educator

Dr Ian Cowell

United Kingdom

Evထlve creative works and Certified CFT trainer

Ian is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy educator and clinician with a particular interest in the management of persistent musculoskeletal pain disorders. His research focus is how person-centred communication is enacted in physiotherapist-patient interactions.

- PhD | MSc Musc. Physio

- Director and clinician - Brook Physio

- Clinicial educator

Prof Peter O'Sullivan

Australia

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer,

creative works co-lead

Pete is internationally recognised as a leading clinician, researcher and educator in musculoskeletal pain disorders. Over the past 20 years, Pete and his team have developed a novel management approach for people with disabling low back pain – called 'Cognitive Functional Therapy'. Pete's passion is to bridge the gap between research and practice – in order to empower researchers, educators and clinicians in the provision of person-centred care for people in pain.

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist*

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- John Curtin Distinguished Professor Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2005)

Dr JP Caneiro

Australia

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer,

creative works co-lead

JP is an emerging leader in the field of chronic pain, particularly the management of back pain and osteoarthritis. He is passionate about mentoring clinicians to ensure the highest level of care is provided in clinical practice. Born and raised in Brazil, JP also speaks Portuguese fluently and is committed to affordable translatable knowledge that is accessible to clinicians regardless of country.

- Specialist Sport Physiotherapist*

- Titled Pain Physiotherapist

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- PhD | MSc Musc. & Sports Physio

- Adjunct Clinical Senior Researcher - Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2013)

Dr Peter Kent

Peter is a musculoskeletal pain researcher and was the lead researcher on the RESTORE trial for people with low back pain. For more than 20 years he practiced as a Physiotherapist & Chiropractor.

- Clinical Epidemiologist

- PhD | Grad.Dip.Manip.Physio | B.App.Sc.(Physio) | B.App.Sc (Chiro)

- Mindfullness teacher

Assoc Prof Kjartan Vibe Fersum

Norway

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- PhD | MSc Musculoskeletal Physio | BSc Physio

- Director and Clinician at Health In the Center (Bergen, Norway)

- Associate Professor at University of Bergen (UIB)

- Lecturer for Musculoskeletal Masters programme (UIB)

- Clinical educator

Assoc Prof Wim Dankaerts

Belgium

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

Wim is a musculoskeletal physiotherapy clinician, researcher and educator with a particular interest in the integration of a multi-dimensional clinical reasoning process and person-centred communication to enhance self-management in patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain disorders.

- Professor of Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy - University of Leuven, Belgium

- PhD – PT – MT

- Clinical Director and Clinician - @PVMT, Tienen, Belgium

- Clinical educator

Kasper Ussing

Denmark

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- Master of Manipulative Therapy (Curtin University)

- Co-owner Spine & Mind Fysio

- Coordinator of Unit for Cross Sectional Cooperation (spinal care) - Spine Centre of Southern Denmark

Gurpreet Singh

United Kingdom

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- BSc | M Research

- Clinical educator

- Guest lecturer University of Coventry and University of Leicester

Dr Chris Newton

United Kingdom

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Consultant Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist and clinical academic at University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire

- PhD | MSc Advanced Musculoskeletal Practice

Irene Stegemejer

Denmark

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- Multidisciplinary Pain Centre, Odense University Hospital

- Co-owner Spine & Mind Fysio

Jannick Johansen

Denmark

Evထlve Certified CFT Trainer

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

- Master in Fitness and Exercise (University of Southern Denmark)

- Co-owner Spine & Mind Fysio

- Bachelor in Physiotherapy, Physiotherapy School in Odense

Just a reminder...

Infographic

From despair to living again

please get in touch.

Professor Peter O'Sullivan

AUSTRALIA

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer, creative works co-lead

Pete is internationally recognised as a leading clinician, researcher and educator in musculoskeletal pain disorders. Over the past 20 years, Pete and his team have developed a novel management approach for people with disabling low back pain – called 'Cognitive Functional Therapy'. Pete's passion is to bridge the gap between research and practice – in order to empower researchers, educators and clinicians in the provision of person-centred care for people in pain.

- Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist*

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- John Curtin Distinguished Professor Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2005)

Dr JP Caneiro

AUSTRALIA

Evထlve director, certified CFT trainer, creative works co-lead

JP is an emerging leader in the field of chronic pain, particularly the management of back pain and osteoarthritis. He is passionate about mentoring clinicians to ensure the highest level of care is provided in clinical practice. Born and raised in Brazil, JP also speaks Portuguese fluently and is committed to affordable translatable knowledge that is accessible to clinicians regardless of country.

- Specialist Sport Physiotherapist*

- Titled Pain Physiotherapist

- Director Body Logic Physiotherapy

- PhD | MSc Musc. & Sports Physio

- Adjunct Clinical Senior Researcher - Curtin University

(as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2013)